Alligator Alcatraz: When History Echoes with a Snarl

Listen to the podcast

There are moments so vile they strip away any illusions of “dog whistles.” Laura Loomer’s sickening tweets calling for “feeding illegals to the gators,” and the subsequent celebration of Alligator Alcatraz in Florida—cheered on by political elites—should be named for what they are: acts of hate designed to terrorize and dehumanize.

Some will try to brush this off as a joke, a marketing ploy, or a bit of red-meat politics. But these words, images, and merchandise are rooted in one of the darkest chapters of American racial terror:

In the 1800s and early 1900s, white newspapers routinely labeled Black children “alligator bait.”

In one horrifying example, Black boys accused of stealing were simply numbered “Alligator Bait #1” and “Alligator Bait #2” instead of being named.

Postcards from Florida showed images of Black toddlers with alligators, captioned “alligator bait,” sold to white tourists as a joke.

In 1912, Black citizens in Chattanooga protested a political campaign’s use of “alligator bait” propaganda on postcards.

And most chilling of all, a 1923 news report described white hunters using naked Black babies as literal live bait to lure alligators in shallow water.

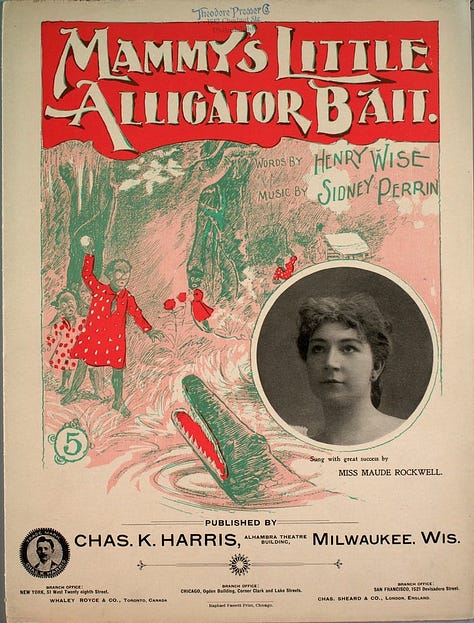

Even songs of the era told the story, with white men writing lyrics about “mammy’s little alligator bait” — warning bad Black children they’d be thrown to the gators.

Some historians debate whether the practice was ever truly widespread. But here’s the brutal truth: it does not matter.The imagery worked as a tool of terror and dehumanization. It reminded Black families that their children could be treated as disposable, animal feed, at the whim of white power.

Fast forward to 2020—Florida banned the “Gator Bait” chant at football games precisely because of these racist roots. The history is recent, known, and undeniable.

So for Loomer to revive that same language in 2025, for politicians to hype “Alligator Alcatraz” with winking glee, is no coincidence. It is a calculated signal. It is a declaration that certain human beings deserve to be devalued, caged, and fed to monsters.

This is not merely rhetorical cruelty. It primes people to treat migrants—like Black children a century ago—as vermin, a food source for beasts. When politicians joke about these atrocities, they encourage a cultural permission slip to commit more violence, to rob entire groups of their humanity, and to profit from their misery by selling merchandise mocking their pain.

It is part of what I call a Prospect Theory of Hate: When people feel their power slipping, they are more willing to take radical, dehumanizing actions to avoid the perceived loss of status. Feeding “illegals” to the gators becomes a metaphorical—and literal—way to maintain a dying hierarchy.

This is why we cannot look away.

They want us to flinch. They want us to look the other way. But we cannot.