Thomas Jefferson: Obsessive Clarity and the Architecture of Civic Design

From the THX Series Hub: Neurodivergence & the Founding of a Nation

“The most valuable of all talents is that of never using two words when one will do.”

—Thomas Jefferson

Jefferson Through a THX Lens

Thomas Jefferson, principal author of the Declaration of Independence, wasn’t a fiery orator or political bulldog. He was a writer, a reviser, a system-builder. If George Washington was the body of the revolution, Jefferson was part of its cognitive architecture.

His contributions reflect an intense focus on Clarity, Value, and Meaning in the THX Utility model. He didn’t just write for the present—he constructed ideas to last centuries.

Neurodivergent Patterns in Jefferson’s Life

Without diagnosing, we can observe behaviors consistent with traits often found in neurodivergent individuals:

Social Withdrawal & Preference for Asynchronous Communication: Jefferson preferred writing letters to face-to-face conversation, even with close allies. This resonates with neurodivergent individuals who favor clarity, control, and processing time.

Obsessive Focus & System Design: He obsessively redesigned Monticello, cataloged native flora, and kept meticulous daily records. These habits reflect cognitive persistence and pattern focus.

Moral Logic vs. Emotional Comfort: Jefferson’s decisions around slavery, though deeply flawed, also showed classic internal contradiction—a relentless drive for logical ideals despite emotional or social realities.

THX Utilities in Jefferson’s Legacy

Clarity: His writing aimed to distill complex ideas into universal truths. "We hold these truths to be self-evident" wasn’t just a phrase—it was an act of engineering clarity from chaos.

Value: Jefferson built value into systems: the University of Virginia, the Library of Congress, and more. He believed in the propagation of knowledge as a civic asset.

Meaning: He believed in self-determination—not just politically, but cognitively. To know, to think, to reason, was a moral act.

Consistency: His worldview had deep internal logic, though that logic didn’t always align with the messy human contradictions of his time.

Closure: His grave inscription names only three achievements: Author of the Declaration, Founder of UVA, and Statute for Religious Freedom. He defined his own legacy with finality.

Prospect Theory in Action

Jefferson was deeply loss-averse when it came to liberty. His writings reveal that he saw any encroachment on civil liberty as a profound loss—more intense than the pleasure of economic gain or national power. This aligns with Prospect Theory’s concept that perceived losses loom larger than equivalent gains.

His resistance to centralized federal power, and insistence on the right to dissent, reflect a nervous system highly tuned to the pain of constraint.

PERMAH in Jefferson’s Life

Before diving into the larger framework of transformation, we can see Jefferson’s own psychological flourishing through the lens of PERMAH:

Positive Emotion: Jefferson found joy in ideas, design, nature, and the cultivation of knowledge.

Engagement: His intellectual immersion—from writing to architecture—shows a mind in constant flow.

Relationships: Often complex, but meaningful; especially through correspondence and philosophical debate.

Meaning: A deep believer in the Enlightenment ideal that reason and liberty could shape a better world.

Achievement: Authoring foundational documents, founding institutions, expanding intellectual capital.

Health: Physical ailments and social withdrawal hint at inner tension; still, he showed cognitive and creative resilience.

Admiration Equation in Jefferson’s Legacy

Jefferson didn’t inspire admiration because he was universally lovable—he inspired it because he mattered. His contributions triggered the components of admiration:

Skill: Crafting elegant, resonant language and founding institutions

Goodness: His ideals of liberty and self-governance

Awe: His wide intellectual pursuits and contributions

Gratitude: For his foundational role in shaping American identity

His contradictions do not erase his influence—they deepen our understanding of what admiration, legacy, and complexity can coexist within a single life.

How the Frameworks Connect: Utility → PERMAH → Admiration

To understand the lasting influence of Jefferson—and others like him—we need to understand how these three frameworks work together.

The 12 Utilities reflect how people assess usefulness, function, and emotional delivery. When those utilities are met, people engage.

PERMAH captures what it means to thrive—not just function. It describes how people experience life when they’re inspired, connected, and purposeful.

The Admiration Equation shows how people go from respecting a system to revering a person. Admiration occurs when usefulness overlaps with identity and aspiration—when someone doesn’t just help us, they shape us.

In Jefferson’s case, this full progression shows how cognitive traits, once given form and utility, create individual and collective flourishing—and leave a legacy that invites both praise and scrutiny.

From Utility to PERMAH to Admiration

Jefferson’s legacy demonstrates how delivering consistent value through utilities can activate flourishing—and ultimately, admiration.

➤ Utility → PERMAH

Clarity fueled Positive Emotion and Meaning—people felt inspired, not confused; they saw themselves in the ideals and believed those ideals were attainable. Clarity made the abstract concrete, and the revolutionary personal.

Value and Meaning supported Engagement—citizens were called into intellectual and moral participation—and gave rise to a sense of Achievement through shared authorship in the democratic experiment.

Closure gave citizens a sense of resolution and legacy—it offered an ending that felt purposeful, not abrupt; it marked transitions with meaning, allowing individuals to feel tethered to a narrative larger than their own lifetime.

➤ PERMAH → Admiration Equation

When utility met identity, Jefferson became admired for:

Skill in articulating Enlightenment ideals

Goodness in advocating self-governance (even if inconsistently applied)

Awe at his intellectual breadth—from architecture to agriculture to education

Gratitude for the enduring documents and ideals he helped define

His admiration was not for his charisma, but for his clarity of mind and civic design. And yet, that clarity came with cost.

The Paradox of Clarity Without Equity

Jefferson is a study in contradictions. He sought liberty while owning slaves. He promoted education while limiting whose voices were heard.

This, too, is worth reflecting on: neurodivergent brilliance is not the same as moral perfection. Clarity of thought is powerful, but without empathy and inclusion, it can architect systems that exclude.

In modern terms: usefulness alone is not enough. If the system only serves some, admiration becomes ambivalence.

Reflection and Challenge

What happens when someone builds a system that outlives them—but not their blind spots?

How do we inherit brilliance with accountability?

How do we design systems today that are both clear and compassionate?

Join the conversation: Where do you see the need for obsessive clarity in your work? And where must clarity yield to inclusion?

Next in the Series

Coming soon: Alexander Hamilton and the electric mind of relentless productivity.

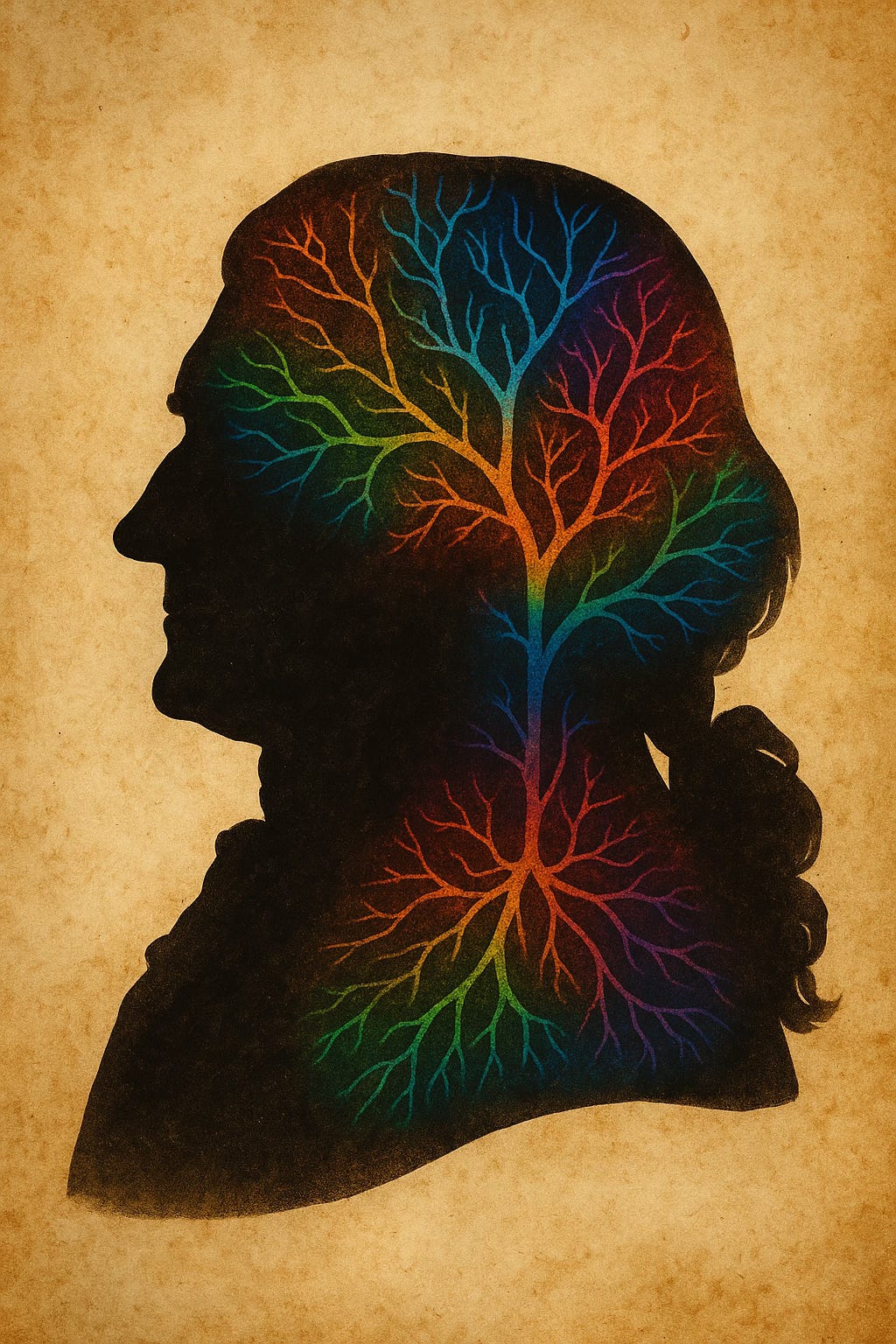

Interpretation:

This image symbolizes Jefferson not as a distant founder, but as a designer of ideas—obsessive, structured, and visionary. The neural patterns suggest cognitive divergence; the architectural elements hint at his systemic mindset. The parchment grounds him in history, while the glow hints at enduring impact. It's not just about what he built—it’s how he thought.